Do "space disinfectant" gadgets really stop flu? (Spoiler: no)

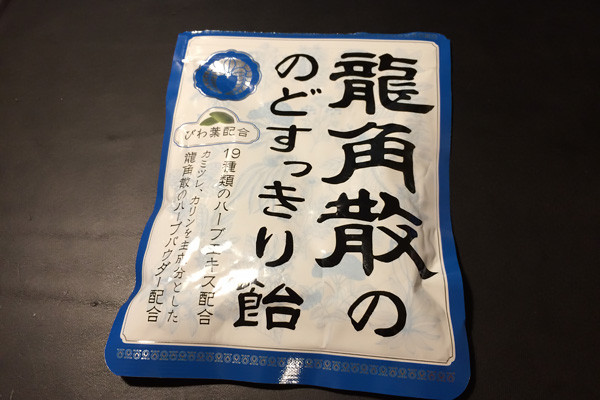

I’m a Japanese writer talking to non-Japanese readers: every winter, Japanese drugstores stack “space disinfectant” gels and neck badges (about ¥1,000). Staff even wear them. They promise to block viruses, odors, pollen—do they work?

I kept thinking: is this like those “titanium” necklaces baseball players wear—feel-good placebo? With small kids I almost bought one (“if it helps at all!”) but held off to dig deeper.

Regulatory smackdown (Japan, 2015)

- Japan’s Consumer Affairs Agency hit 17 companies with penalty orders for exaggerated “space disinfection” ads (claims lacked evidence).

- The National Consumer Affairs Center had already warned in 2010: some products released too little chlorine dioxide to matter, others too much and stank, and “food additive, so safe” wording could mislead.

The marketing claims (packaging highlights)

- “Wears like a shield; purifies 1 m³ around you”

- “Space disinfection,” “virus removal,” “odor removal,” “anti-mold,” “pollen countermeasure”

The graphics show a force field around the model—almost “banish evil spirits!” level hype.

What’s inside (Cleverin and similar)

- Main ingredient: chlorine dioxide, a chlorine-family gas used for bleaching/disinfecting.

- Related to household bleach (sodium hypochlorite) in behavior; can corrode metals and electronics if concentrated.

Daikyo Pharmaceutical (Seirogan’s “trumpet” brand) popularized Cleverin in 2005; other firms followed. An industry group (“Japan Chlorine Dioxide Industry Association”) formed, but no product is approved as a drug in Japan—so they’re sold as “misc goods,” advertised like medicines, which is the problem.

An earlier consumer test (2010)

The consumer center tested tabletop canisters (Cleverin, “Wiclear”) and found:

- Disinfecting effect in real rooms was uncertain (sometimes too little gas, sometimes overpowering odor).

- “Food additive, so safe” wording could mislead.

- “Prevents influenza” is a drug claim—out of bounds for household goods.

- Chlorine gas can corrode metal/electronics; keep away from babies’ reach.

Both companies were told to revise their copy; they did.

Lobbying and the legal gap

Wikipedia notes: even if chlorine dioxide can inactivate viruses, claiming infection prevention requires drug approval—none of these have it. That mismatch (sold as “goods,” advertised like drugs) led to the 2015 penalties.

A small study that hinted at benefit

A 2010 paper (Japan Environmental Infection Society) tried low-dose chlorine dioxide in JSDF barracks (roughly one canister per 6-tatami room). The intervention group had fewer “influenza-like illness” cases. Authors suggested the gas might inactivate droplets before inhalation—but added “more studies needed.” One exploratory result ≠ proof.

Safety and copycat risks

- Chlorine dioxide does disinfect, but real-world dose/effect and long-term safety in occupied rooms are still unclear.

- Hypochlorite “space” badges (a different ingredient) even caused chemical burns when sweat made them wet; Japan’s consumer agency told people to stop using them. Cases included a 6-year-old who slept with one by her face and an infant with red, itchy palms after handling one.

- Chlorine gases can corrode metal/electronics; labels bury that in fine print.

With kids bringing home colds and noro, a ¥1,000 badge is tempting. But if it’s weak, you still get sick; if it’s strong, you risk irritation/corrosion. I’ll stick to boring basics until safety/efficacy are clearer.

2022: Another enforcement hit (Cleverin)

On 2022-04-15 Japan’s Consumer Affairs Agency issued a corrective order (and surcharge) to Daikyo Pharmaceutical for “Cleverin” 60 g / 150 g tabletop products, ruling their claims were misleading under the Act against Unjustifiable Premiums and Misleading Representations.

Takeaway

- “Space disinfectant” gadgets: effect unproven, often overclaimed.

- Neck-worn types can be risky (skin/contact accidents reported with some formulas).

- For flu/cold: handwashing, masks as appropriate, ventilation, surface cleaning—old-school but reliable.

Evidence that a badge or jar can disinfect the air around you is weak. Use proven steps instead: handwashing, masks when appropriate, ventilation, and surface disinfection where it counts.