Thoughts on “The Courage to Be Disliked” and “The Courage to Be Happy”

These were trending around me, so I read them. The core claim: “All human problems come from interpersonal relationships. If you overcome that, you can change and be happy.”

The books are small and structured as dialogue between a troubled youth and a guiding philosopher, easy to read—but the philosopher’s Adlerian ideas are abstract and meander, making me wonder “Does this really hold up?” I read twice and wrote notes to organize my thoughts.

Turns out I was already doing a lot of Adlerian stuff

Long ago I read Dale Carnegie’s “How to Stop Worrying and Start Living” and “How to Win Friends and Influence People.” They say “You can’t change people, so change yourself.” I agreed and started living that way. Carnegie was influenced by Adler, so the roots overlap.

Younger me thought “I’m objectively right; that person is wrong; I must correct them.” With surface-level things you might succeed, but you can’t change the deeper layers. I blamed my lack of persuasion, then realized those layers aren’t really changeable—so I stopped stressing over it.

I’m also naturally shy and used to “care about others’ eyes,” but around 30 I thought: “Wait, I expected thirtysomethings to be more adult; we’re still kids,” “Fortysomethings aren’t that different,” “If my active years are only ~30 more, why waste them worrying?” So I loosened up.

In other words, “your life is yours” within not harming others. Reading Adler after that left me thinking, “Okay, mostly already doing this.”

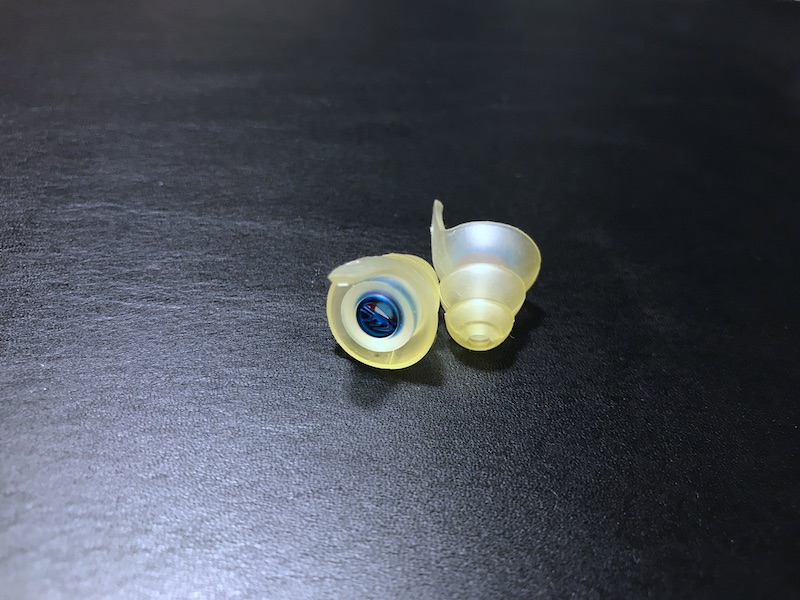

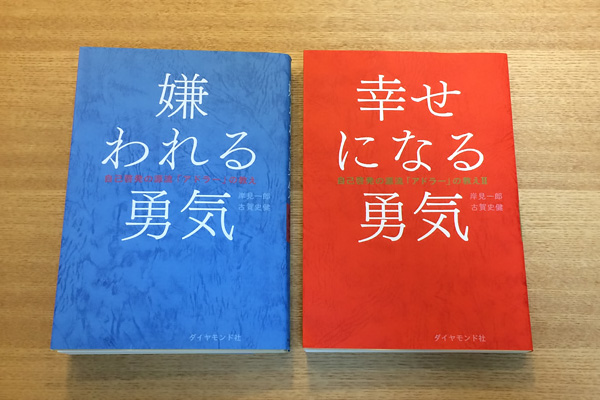

The blue book: The Courage to Be Disliked

Chapters:

- Deny trauma

- All problems are interpersonal

- Discard others’ tasks

- Where is the center of the world?

- Live earnestly in the “here and now”

Deny trauma

The opening “deny trauma” hits hard; without that lens you might recoil. I used to think “Things went wrong because of past bad events.” That’s backward-looking and binding yourself to the past, and the book immediately rejects it. Macho! It says you define yourself by how you interpret past events.

It reminded me of the Japanese TV show “Shikujiri Sensei,” where fallen celebrities return after digesting their mistakes—turning trauma into fuel.

Not so much erasing trauma as reframing it: face forward or you’ll run backwards; at least look ahead so good things can happen.

Lifestyle

This chapter introduces “lifestyle.” Even temperament and personality—anger, shyness, courage—are framed as “chosen.” The philosopher insists you “decided not to change.” He even says you picked this around age 10. I agree partly, but think environment matters too. Some start low and spiral, others correct; some start high and still spiral, or climb higher. As I wrote that, I realized I was echoing the philosopher. Hmm.

All problems are interpersonal

This rings true. Annoyance usually involves comparison—to someone “better.” The book notes you wouldn’t fret if you were alone in space. Agreed.

Think of a carefree rural life, then visiting the city and comparing your “rough edges” to sleek urbanites—that jolt.

Common advice: “No one is watching you.” True—unless someone is very odd, we ignore and forget them. The book says, “The inferiority we suffer is a subjective interpretation, not objective fact.” Right.

Inferiority feelings vs. inferiority complex

Inferiority feeling: “I look sloppy in town.” Inferiority complex: “I look sloppy because I’m from the countryside”—a rationalized excuse. Feeling inferior isn’t bad: if it bothers you, improve; if not, nothing happens next time.

I’ve often fallen into the complex side—blaming circumstances. Not helpful.

Superiority complex

Another term: bragging to mask inferiority—“My friend’s friend is a celeb,” “I partied with a TV talent.” Easily spotted on social media. Exaggerated resumes or head-to-toe designer outfits fit. All-Prada might read as “insecure?”

The book says:

(Paraphrased) Wearing jewels on every finger isn’t about taste; it’s inferiority and superiority complex.

Borrowing authority means living by others’ values, living others’ lives.

People obsessed with status games likely live here.

Suffering brag

Called “a sharpened superiority through inferiority.” Being “special” via misfortune, using unhappiness to stand above and control others. I thought of infamous internet figures who weaponize victimhood. Yikes.

How I cope with my inferiority

The book says:

- Inferiority feelings are healthy.

- Compare to your ideal self, not others.

- Don’t race anyone; just face forward and walk.

My own mantra:

- (Current) me can’t—yet. But who knows in 10 years?

If 10,000 hours builds expertise, then when I see a peer excel, I think “They put in their 10k while I read manga.” If I truly cared, I’d keep at it for a decade; even 10 minutes a day over 10 years exceeds 3,000 hours—plenty if they stopped at 10k. Time adds optimism.

Discard others’ tasks

Boom: “Deny approval-seeking.” Live by your decisions, not others’ evaluations. Stoic—reminds me of hurdler Dai Tamesue, who self-trained and self-critiqued en route to medals. If the world were 100 Tamesues, conversation would be sparse (bias showing).

“Task separation” also appears throughout: identify whose task a problem is and only tackle yours. Adlerian psych avoids intervening in others, so you cut away what’s not yours.

This reminded me of the problem-solving book “Are Your Lights On?”

Old but great for finding the right problem to solve. Techniques are useful to know.

Freedom is being disliked

Midway we get the title: “Unless you’re willing to be unapproved and even disliked, you can’t live your own way.”

It sounds inflammatory, but it’s really “Don’t be ruled by others’ eyes.” Those “eyes” include parents, which is a fresh angle.

But living freely under constant parental pressure is hard. Same with schools/companies where you share time and space. Keeping polite distance until people file you under “that’s just them” helps.

Where is the center of the world?

This is about meta-perspective. Kids only see through their own eyes; as you grow you can view yourself from above (I picture a security camera).

When you crave approval, your world stays self-centered. With mental room, your viewpoint rises and you see yourself plus others.

Thinking about viewpoint height made me picture a snail: poke it and its eyes retract; leave it and they stretch out. I want to be a tough snail.

Listen to the larger community

We all belong somewhere; when stuck, shift perspective to a larger community. The book doesn’t list them, but here’s how I imagine it:

(larger) Universe >> Earth >> World >> Country >> Local community >> School/Company >> Family (smaller)

If family feels off, look to school/work; if school/work feels off, look to local groups (lessons, clubs, city events, park radio calisthenics crew, fishing buddies, etc.). SNS could be a layer, though it’s unstable.

As a student I thought school was my whole world. Realizing other circles helps. As an adult, I joined hobby groups and enjoy “lab hopping” until one fits.

Live earnestly in the “here and now”

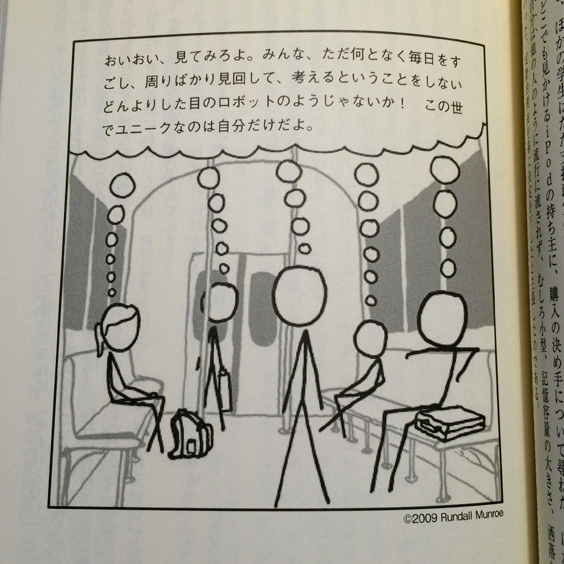

We fixate on others’ eyes, assume we’re “special,” and think we’re too unique to blend in.

Most of us aren’t special. Grind steadily. High achievers stack small repetitions; 10k hours to reach crazy heights. Rare prodigies can still be passed if they coast. Pro gamer Daigo Umehara wrote about being big as a kid, then losing fights in middle school after gaming too much.

In The Art of Choosing (link), surveys asking “Are you above or below average?” get “average or a bit above” from most. Humans default to that self-view. Wanting to be “more special” can become a swamp. Accept “ordinary” and have the courage to own it.

Dance through life

“Life is a chain of instants, danced through in the here and now.”

Don’t stare at past trauma or compare outward; focus on today’s dance and you’ll end up somewhere unexpected. Dropping lofty goals into daily grains keeps it doable; tiny stacks over time create big results—just not on a high-school-timeline.

Steve Jobs’ “connecting the dots” speech is similar: put dots in many places; later, unrelated dots connect in surprising ways.

Everything is up to you. Don’t stagnate—take a step. The youth in the book keeps saying “If I could, I would!” but ultimately it’s personal. You can lead a horse to water; you can’t make it drink. Harsh, harsh!

What happened to the troubled youth?

He’s angry almost the whole time—argues, occasionally concedes, then rages again—and suddenly has a lightning-bolt epiphany and leaves. For me it felt like calmly watching curveballs, then getting beaned by a fastball—ending abruptly.

The red book: The Courage to Be Happy

Same characters; the youth returns as a teacher, having tried Adler and “failed,” still mad. He rants until the end, then again gets zapped. These aren’t translations, yet they read like a Platonic dialogue—makes me curious.

The blue book focused on personal mindset; the red shifts to living with others. With the youth now a teacher, there’s more on education. This part didn’t click for me, even on a second read.

When the youth complains about no romantic prospects and is told “Live in the now,” it echoed something I wrote earlier:

Oddly, “I want a boyfriend/girlfriend!” rarely works, but when you dive into something you love, encounters appear. — Butter coffee and dieting

Money, love, info—people who give openly tend to receive more (if you can call it a return). Also, it’s less stressful than hunting.

Across both books, a summary might be: “Live freely without overvaluing others’ eyes; give without fixating on returns; good things will follow.” The red ending even felt a bit like Evangelion’s Human Instrumentality; the youth yells “It’s a religion!” and honestly I partly agreed.

It isn’t religion; the core makes sense and isn’t harmful. But when Adler introduced “community feeling,” some disciples left. Full understanding probably takes multiple reads.

Live like a manga protagonist

Adler seems to say, “Don’t live by comparisons; live your own life.” That means setting an ideal self and closing the gap, but I never had a clear ideal. No athlete/idol to emulate; only fragmented role models (“strong in Japanese like Kato; strong in PE like Suzuki”)—nothing holistic.

So I thought: live like a favorite manga protagonist. They usually mirror my ideals, and because they’re fiction, they lack glaring flaws. Not gods, but stable ideals.

Not dark antiheroes like Ushijima the Loan Shark—more classic shonen.

“When was your prime, Dad? Nationals? Mine… mine is right now!”

Slam Dunk’s Hanamichi was physically gifted but new to basketball, so he drilled basics forever. He’s fundamentally positive, stacks practice and games, and grows steadily—leading to that line in the Sannoh game.

Maybe too high a bar for me, but heading toward those characters feels right. When the gap hurts, I can at least aim for Kogure-level consistency (and he put in three years).

Incidentally, Mitsui lines up with the “five stages of problem behavior” in Adler; his moment of “I want to play basketball” matches a point in the book—made me go “oh!”